You can illustrate a lot with a map. Here's a good one, for example:

I also use the Perry-Castaneda Map Library frequently.

The UN Cartographic Service is also excellent.

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

How to Cut and Run

I recently met William Odom at the IISS conference in Geneva. I have a great deal of admiration for him as a soldier and a scholar. He has been making the argument that the United States should cut his losses and get out of Iraq practically since the day the occupation began. He reprises it here: How to Cut and Run.

Odom is not your typical anti-Iraq war type, as you'd expect for a former head of the NSA and Army intelligence chief. Most untypically, he doesn't just say get out but discusses how to do it, it amounts to a four step programme:

1. admit that we screwed up

2. involve Iraq's neighbours

3. cooperate with Iran, drop resistance to its nuclear arms programme

4. focus on Palestinian issue as a foundation for Middle East peace.

I find it difficult to agree with him on points 2, 3 & 4. Iraq's neighbours are already involved. I think we don't know nearly enough about how Islam in general and Iran in particular understand the utility of nuclear force--put differently how they conceive of deterrence--to feel sanguine about an Iranian bomb. And as far as I'm concerned the less attention paid to Israel-Palestine by everyone the better. That conflict has been prolonged and exacerbated by every past intervention not hastened toward its resolution.

I am reluctantlly in agreement with point 1, however. As Odom argues:

'Rapid troop withdrawal and abandoning unilateralism will have a sobering effect on all interested parties. Al Qaeda will celebrate but find that its only current allies, Iraqi Baathists and Sunnis, no longer need or want it. Iran will crow but soon begin to worry that its Kurdish minority may want to join Iraqi Kurdistan and that Iraqi Baathists might make a surprising comeback.

Although European leaders will probably try to take the lead in designing a new strategy for Iraq, they will not be able to implement it. This is because they will not allow any single European state to lead, the handicap they faced in trying to cope with Yugoslavia's breakup in the 1990s. Nor will Japan, China or India be acceptable as a new coalition leader. The U.S. could end up as the leader of a new strategic coalition — but only if most other states recognize this fact and invite it to do so.'

One of the most disastrous outcomes of the war has been the collapse of Western unity. It's not as though it hasn't happened before but I don't think the split has ever been this profound.

Odom is not your typical anti-Iraq war type, as you'd expect for a former head of the NSA and Army intelligence chief. Most untypically, he doesn't just say get out but discusses how to do it, it amounts to a four step programme:

1. admit that we screwed up

2. involve Iraq's neighbours

3. cooperate with Iran, drop resistance to its nuclear arms programme

4. focus on Palestinian issue as a foundation for Middle East peace.

I find it difficult to agree with him on points 2, 3 & 4. Iraq's neighbours are already involved. I think we don't know nearly enough about how Islam in general and Iran in particular understand the utility of nuclear force--put differently how they conceive of deterrence--to feel sanguine about an Iranian bomb. And as far as I'm concerned the less attention paid to Israel-Palestine by everyone the better. That conflict has been prolonged and exacerbated by every past intervention not hastened toward its resolution.

I am reluctantlly in agreement with point 1, however. As Odom argues:

'Rapid troop withdrawal and abandoning unilateralism will have a sobering effect on all interested parties. Al Qaeda will celebrate but find that its only current allies, Iraqi Baathists and Sunnis, no longer need or want it. Iran will crow but soon begin to worry that its Kurdish minority may want to join Iraqi Kurdistan and that Iraqi Baathists might make a surprising comeback.

Although European leaders will probably try to take the lead in designing a new strategy for Iraq, they will not be able to implement it. This is because they will not allow any single European state to lead, the handicap they faced in trying to cope with Yugoslavia's breakup in the 1990s. Nor will Japan, China or India be acceptable as a new coalition leader. The U.S. could end up as the leader of a new strategic coalition — but only if most other states recognize this fact and invite it to do so.'

One of the most disastrous outcomes of the war has been the collapse of Western unity. It's not as though it hasn't happened before but I don't think the split has ever been this profound.

Monday, October 30, 2006

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

Virtual war

I'm fascinated by the way in which technological change is affecting modern warfare. By and large my research has focused on changes at 'the pointy end'. So, for instance, I've been writing a lot about the Revolution in Military Affairs and its derivative concepts Network-Centric Warfare and Information Warfare. But I'm more and more interested these days not just in how we fight wars but how we conceptualize them societally, which ultimately feeds back into the way we fight and vice versa. In other words, I'm thinking a little less about changes at the pointy end of the spear and a little more about how the spear as a whole is changing. Specifically, I'm researching two things which are a direct outgrowth of the IT revolution.

The first is the phenomenon of milblogging, ie a blog about war like this one, but written by a soldier in the field as opposed to an academic in a comfy London office. I think the impact of milblogging is significant in several respects. For one thing it makes it all the more difficult for theatre commanders to establish and control a narrative of the conflict. There's been a lot of discussion over the years about the impact of the media on warfare, but we are only slowly waking up to the fact that it is now conceivable for soldiers to simply 'cut out the middle man' and report directlly their experience through the medium of a blog. Indeed this is already somewhat the case, as you can see in this article by uber-milblogger Michael Yon in which he points out that there are just 7 embedded reporters in Iraq right now. I find that surprisingly low. We're not just talking about text either, soldiers post videos and photos. There's a vast and growing genre of such 'tribute' videos as this one, almost always set to Heavy Metal tracks it seems, army humour like this British minor classic, as well gun camera footage such as this (warning: graphic), over on YouTube . Most is pretty tame illustrative of the long recognized fact that 99% of the experience of war is boredom--sitting around waiting; some of it is pretty dreadful (link is to an article).

So what's new about any of this? Well, nothing and a lot, depending on your viewpoint. Dreadful things have always happened in war. Cameras small enough to fit in a soldier's pocket have been around for years. What's different is that in the Nokia Age images which in the old days might have ended up in a shoebox in the attic are now shared and infinitely reproduced digitally over the Internet. 'Warfare', wrote Andrew Marr writing after the publication of stories based on photos--fake as it turned out--about abuse of Iraqi prisoners by British troops 'has always depended on a rampart of silence, a wall of willed incomprehension, between civilians at home and those killing. In a small way, the arrival of digital photographs has broken through that wall.' We're beginning to see how this changes things. I suspect, among other things, a main effect we are seeing is maintaining political will. We already, according to some, suffer from a societal attention deficit disorder. This would seem to be a complicating factor.

The second, and related, thing which strikes me as potentially quite significant is the increasing sophistication of video games. There's a very practical military dimension to this: games are an increasingly invaluable training aid. But there's a nother dimension: computer games like 'America's Army' or, somewhat less so, XBox's 'Full Spectrum Warrior', play a role in society akin to the World War 2 Frank Capra series of films 'Why we Fight'. I wouldn't want to overstretch the argument here but at least in some respects there is an apparent convergence between war and video games. James Der Derian's Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment covers some of this ground, but is rather flawed . He's a good writer, for a post-modernist, but not terribly convincing on operational military matters . Ed Halter's From Sun Tzu to XBox: War and Video Games, is better though it's appeal is possibly greater to gamers than soldiers. But this US Army video about the Future Combat System is a nice illustration of the point. I wonder if army recruiters ask applicants if they play a lot of video games and if they do whether that's considered a good thing. I suspect it would. I read somewhere (can't remember) that soldiers who had played a lot of first person shooter games were ideal for operating the remote weapons on armoured humvees. They were less likely to get disoriented and more confortable with the constant scanning necessary for useful observation through a narrow field of view.

What's really interesting, however, is not the tactical shoot 'em up games but games such as the one described in thsi article which are more about real-world challenges involving moral complexity, problem solving and cultural understanding. I suspect that this sort of thing is more valuable in the long run. Actually, I think I'd like too do something like thsi in our programme!

The first is the phenomenon of milblogging, ie a blog about war like this one, but written by a soldier in the field as opposed to an academic in a comfy London office. I think the impact of milblogging is significant in several respects. For one thing it makes it all the more difficult for theatre commanders to establish and control a narrative of the conflict. There's been a lot of discussion over the years about the impact of the media on warfare, but we are only slowly waking up to the fact that it is now conceivable for soldiers to simply 'cut out the middle man' and report directlly their experience through the medium of a blog. Indeed this is already somewhat the case, as you can see in this article by uber-milblogger Michael Yon in which he points out that there are just 7 embedded reporters in Iraq right now. I find that surprisingly low. We're not just talking about text either, soldiers post videos and photos. There's a vast and growing genre of such 'tribute' videos as this one, almost always set to Heavy Metal tracks it seems, army humour like this British minor classic, as well gun camera footage such as this (warning: graphic), over on YouTube . Most is pretty tame illustrative of the long recognized fact that 99% of the experience of war is boredom--sitting around waiting; some of it is pretty dreadful (link is to an article).

So what's new about any of this? Well, nothing and a lot, depending on your viewpoint. Dreadful things have always happened in war. Cameras small enough to fit in a soldier's pocket have been around for years. What's different is that in the Nokia Age images which in the old days might have ended up in a shoebox in the attic are now shared and infinitely reproduced digitally over the Internet. 'Warfare', wrote Andrew Marr writing after the publication of stories based on photos--fake as it turned out--about abuse of Iraqi prisoners by British troops 'has always depended on a rampart of silence, a wall of willed incomprehension, between civilians at home and those killing. In a small way, the arrival of digital photographs has broken through that wall.' We're beginning to see how this changes things. I suspect, among other things, a main effect we are seeing is maintaining political will. We already, according to some, suffer from a societal attention deficit disorder. This would seem to be a complicating factor.

The second, and related, thing which strikes me as potentially quite significant is the increasing sophistication of video games. There's a very practical military dimension to this: games are an increasingly invaluable training aid. But there's a nother dimension: computer games like 'America's Army' or, somewhat less so, XBox's 'Full Spectrum Warrior', play a role in society akin to the World War 2 Frank Capra series of films 'Why we Fight'. I wouldn't want to overstretch the argument here but at least in some respects there is an apparent convergence between war and video games. James Der Derian's Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment covers some of this ground, but is rather flawed . He's a good writer, for a post-modernist, but not terribly convincing on operational military matters . Ed Halter's From Sun Tzu to XBox: War and Video Games, is better though it's appeal is possibly greater to gamers than soldiers. But this US Army video about the Future Combat System is a nice illustration of the point. I wonder if army recruiters ask applicants if they play a lot of video games and if they do whether that's considered a good thing. I suspect it would. I read somewhere (can't remember) that soldiers who had played a lot of first person shooter games were ideal for operating the remote weapons on armoured humvees. They were less likely to get disoriented and more confortable with the constant scanning necessary for useful observation through a narrow field of view.

What's really interesting, however, is not the tactical shoot 'em up games but games such as the one described in thsi article which are more about real-world challenges involving moral complexity, problem solving and cultural understanding. I suspect that this sort of thing is more valuable in the long run. Actually, I think I'd like too do something like thsi in our programme!

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

Gloom all around

Niall Fergusson joins the doomsayers in the LA Times today with an article entitled 'America's Brittle Empire'. He argues that the US is a 'strategic couch potato' sufferinga crucial financial deficit, attention deficit, and manpower deficit. Thus he concludes,

In short, I'm unconvinced.

In short, we seem doomed by domestic politics and demography to re-enact Vietnam in Iraq. The only question is what age the 300-millionth American will be when the last American is airlifted out.I think the manpower deficit is crucial. Financial deficit is crucial too--but this can change rapidly. I'm confused by attention deficit though. His last line basically says we'll be there for another 18 years before we admit defeat which doesn't strike me as attention deficit disorder so much as repetitive brain injury caused by too much pounding one's head upon a brick wall.

In short, I'm unconvinced.

Happy UN Day!

Today is UN Day. Hurrah! A whole day to celebrate its achievements. Where to start? There's so many:

Nice photo. I think it's particularly significant in light of the fact that yesterday was the 23rd anniversary of this event.

Nice photo. I think it's particularly significant in light of the fact that yesterday was the 23rd anniversary of this event.

An attack committed by the precursor to Hezbollah headed by Nasrallah.

An attack committed by the precursor to Hezbollah headed by Nasrallah.

UPDATE 25 October 2006:

OK, I was harsh on the UN. Theo has promised to come by and correct me. In the meantime, let me get in another dig. There was a good joke going around when they were debating who would be the next General Secretary after Kofi Annan. Some wags proposed Tony Soprano:

He'd get more done and steal less!

But in the spirit of fairness I'll acknowledge that financial rectitude in Iraq hasn't exactly been improved that much since the occupation made Oil for Food redundant: Mother of all heists.

- its swift and decisive action to halt Rwandan genocide

- its stolid defence of the Srebrenica safe haven

- its scrupulously upright management of the Oil-for-Food scheme

- its gallantry towards Congolese refugess under its protection

Nice photo. I think it's particularly significant in light of the fact that yesterday was the 23rd anniversary of this event.

Nice photo. I think it's particularly significant in light of the fact that yesterday was the 23rd anniversary of this event. An attack committed by the precursor to Hezbollah headed by Nasrallah.

An attack committed by the precursor to Hezbollah headed by Nasrallah.UPDATE 25 October 2006:

OK, I was harsh on the UN. Theo has promised to come by and correct me. In the meantime, let me get in another dig. There was a good joke going around when they were debating who would be the next General Secretary after Kofi Annan. Some wags proposed Tony Soprano:

He'd get more done and steal less!

But in the spirit of fairness I'll acknowledge that financial rectitude in Iraq hasn't exactly been improved that much since the occupation made Oil for Food redundant: Mother of all heists.

Monday, October 16, 2006

Wierder than wierd

Good Nyborg:

Canada troops battle 10-foot Afghan marijuana plants

I want to see the campaign medal for this one.

Canada troops battle 10-foot Afghan marijuana plants

I want to see the campaign medal for this one.

Thursday, October 12, 2006

Memory lane

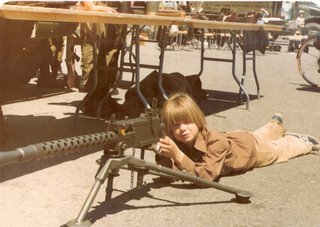

Over on Theo's blog I was chatting about non-standard uses of military technology which got me reminiscing a bit about a happy day in my my short spell as a soldier on the range with a heavy machine gun. Thankfully, I've never fired one in anger, let alone had anyone fire at me! I still think, however, that there're are few things more stress relieving than machine-gunning. Pounding a punching bag pales in comparison. Rather than repeat myself, go look if you've a mind to.

Anyway, I promised to post a picture if I could find it. I couldn't find the exact one I was looking for--that one was with a .50 cal which makes this one look like a bit of a pipsqueak. But I found this one of me on the same day with a .30 cal (actually rechambered for 7.62mm), ca. 1988 (I'm the trigger man):

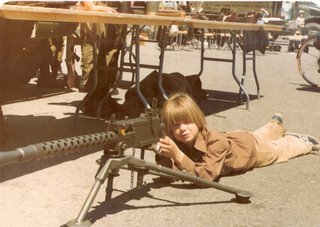

But then while strolling down memory lane I came across this picture, me ca. 1974:

I'd forgotten about that one. This illustrates a few things about me, I think. For example, I'm morbidly goal-oriented. I generally end up where I intended going, eventually, even if I forget having resolved on a plan. The subconscious is a wonderful thing! This is also how I ended up teaching in the Department of War Studies. I decided just after that first picture was taken that I'd better go to university because soldiering in the Canadian Forces wasn't going to be very satisfying for me after all. I think what clinched it was that it's the same damn gun in both pictures, and it was old in 1974. I suspect I took the lesson that I was taking the idea of warfighting a little more seriously than the people paying me were. So, I managed to convince the army to pay for me to go to university where among the first books I read was The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy by Lawrence Freedman, Professor of War Studies. Now that's a cool thing, says I. Next thing I know here I am telling you to read something cool. If I could just get them to install a heavy machine gun in my office--I'd machinegun for peaceful purposes only, promise!--my life would be complete.

Hey, you army guys should invite me on a firepower demo. It might increase your grade. Wait. Damn! I'm teaching civilians and air force guys this term. Hmmm... if I get a ride in a jet I could perhaps an arrange a degree to arrive by first class post. ;)

Anyway, I promised to post a picture if I could find it. I couldn't find the exact one I was looking for--that one was with a .50 cal which makes this one look like a bit of a pipsqueak. But I found this one of me on the same day with a .30 cal (actually rechambered for 7.62mm), ca. 1988 (I'm the trigger man):

But then while strolling down memory lane I came across this picture, me ca. 1974:

I'd forgotten about that one. This illustrates a few things about me, I think. For example, I'm morbidly goal-oriented. I generally end up where I intended going, eventually, even if I forget having resolved on a plan. The subconscious is a wonderful thing! This is also how I ended up teaching in the Department of War Studies. I decided just after that first picture was taken that I'd better go to university because soldiering in the Canadian Forces wasn't going to be very satisfying for me after all. I think what clinched it was that it's the same damn gun in both pictures, and it was old in 1974. I suspect I took the lesson that I was taking the idea of warfighting a little more seriously than the people paying me were. So, I managed to convince the army to pay for me to go to university where among the first books I read was The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy by Lawrence Freedman, Professor of War Studies. Now that's a cool thing, says I. Next thing I know here I am telling you to read something cool. If I could just get them to install a heavy machine gun in my office--I'd machinegun for peaceful purposes only, promise!--my life would be complete.

Hey, you army guys should invite me on a firepower demo. It might increase your grade. Wait. Damn! I'm teaching civilians and air force guys this term. Hmmm... if I get a ride in a jet I could perhaps an arrange a degree to arrive by first class post. ;)

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

Military history website

I thought I'd mention a website I visit fairly frequently and comment on occasionally: Blog them out of the stone age It was started and is still run by Professor Mark Grimsley, a historian at Ohio State University and alumnus of KCL War Studies, with the contribution now of Anthony Cormack, a current BA student in the department (very clever). It's a fairly eclectic site in terms of topics it covers but always interesting. Have a look.

Learning the lingo

In our discussion group we were talking about various military terms and concepts, particularly acronyms, which make it difficult sometimes for the layman to make sense of what is being said. Acronyms, which the military LOVES, are a particular pain in the neck. In the main, these are pretty obvious, eg., SAM (Surface to Air Missile), ICBM (InterContinental Ballistic Missile), C2 (Command and Control), or relatively straightforward to work out, eg., PGM (Precision Guided Munition), UAV (Unmannned Aerial Vehicle), but sometimes they can be pretty arcane/bizarre, eg., APFSDSDU, LANTIRN, C4I2SR, etc. It's useful to absorb some of this lexicon; in general, however, ignore the roccoco ones--they're often esoteric, change rapidly, and there's THOUSANDS of 'em! If you're really stumped and need to know you can check this glossary.

It's vastly more important that you familiarize yourself with military concepts for which this department of defense Dictionary of Terms is somewhat useful, if limited--the definitions are occcasionally sphinx-like in their terseness. What you really must do, if you've no direct military experience (actually, even if you do), is to read military history--lots of it. In the meantime this National Public Radio site is a good primer. There are some good interviews at the end too.

And don't be shy about encyclopaedias either. As I mentioned in an earlier post on Wikipedia they are often a good place to START your research (just don't end it there). You should all be very, very familiar with the ISS website by now. Have a look there now; this time click on 'databases'. Then search for 'Oxford reference on-line'. Go there with your Athens password. This is a very handy resource. You can just do a 'quick search'. For example, try searching for 'Revolution in Military Affairs'. The first hit should be an article in the Oxford Companion to Military History on 'Military Revolution'. Take a shufti.

Go back to the main page. You'll see subject references: military history, history, politics and social sciences, are all useful for us. But there's more: maps, quotations, dictionaries... I find the Timelines quite a useful reminder of the grand sequence of events. What I like particularly about on-line encyclopaedias is the ease with which linkages between concepts can be seen and explored. You start looking for Revolution in Military Affairs and three clicks later you're reading about the battle of Cunaxa. The on-line Oxford Companion to Military History is supremely handy in this respect.

Why is this important? Well, it's likely to contribute to your grade obviously. But it can also help you to look incredibly superior by pointing out the incredible incredulousness of many professional journalists do when talking about military matters. This is an important social service for you as specialists and also rather fun. Theo, in a recent post about the Korean nuclear test being a dud (which, incidentally, I bloggged yesterday. What's up with that Theo? You've got to be quicker with your blogbutton). I think this article describing a street battle in Kifl (via One Hand Clapping) is a lovely example of gullibility in action:

It's vastly more important that you familiarize yourself with military concepts for which this department of defense Dictionary of Terms is somewhat useful, if limited--the definitions are occcasionally sphinx-like in their terseness. What you really must do, if you've no direct military experience (actually, even if you do), is to read military history--lots of it. In the meantime this National Public Radio site is a good primer. There are some good interviews at the end too.

And don't be shy about encyclopaedias either. As I mentioned in an earlier post on Wikipedia they are often a good place to START your research (just don't end it there). You should all be very, very familiar with the ISS website by now. Have a look there now; this time click on 'databases'. Then search for 'Oxford reference on-line'. Go there with your Athens password. This is a very handy resource. You can just do a 'quick search'. For example, try searching for 'Revolution in Military Affairs'. The first hit should be an article in the Oxford Companion to Military History on 'Military Revolution'. Take a shufti.

Go back to the main page. You'll see subject references: military history, history, politics and social sciences, are all useful for us. But there's more: maps, quotations, dictionaries... I find the Timelines quite a useful reminder of the grand sequence of events. What I like particularly about on-line encyclopaedias is the ease with which linkages between concepts can be seen and explored. You start looking for Revolution in Military Affairs and three clicks later you're reading about the battle of Cunaxa. The on-line Oxford Companion to Military History is supremely handy in this respect.

Why is this important? Well, it's likely to contribute to your grade obviously. But it can also help you to look incredibly superior by pointing out the incredible incredulousness of many professional journalists do when talking about military matters. This is an important social service for you as specialists and also rather fun. Theo, in a recent post about the Korean nuclear test being a dud (which, incidentally, I bloggged yesterday. What's up with that Theo? You've got to be quicker with your blogbutton). I think this article describing a street battle in Kifl (via One Hand Clapping) is a lovely example of gullibility in action:

The officers said the tank unit fired two 120 mm high velocity depleted uranium rounds straight down the main road, creating a powerful vacuum that literally sucked guerrillas out from their hideaways into the street, where they were shot down by small arms fire or run over by the tanks.

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

Nork Nukes

So, the buzz of course is about North Korea's nuclear test. You've seen the news, no need for me to link to the main reports. You may not have seen this intriguing theory: the test was a dud; North Korean nuclear scientists are now officially the worst ever.

I don't know enough to judge the science in these claims. I've been meaning to ask Prof Peter Zimmermann here in the Department of War Studies who does have that knowledge. Unfortunately, he's busy talking to journalists who aren't asking the right questions. Damn typical journos! I await enlightenment.

In the meantime, I'm amusing myself with question what does it matter? Answer (thus far): less than you might think.

The thing is that having nukes is not really as useful a thing as active proliferators reckon it is. It doesn't really expand your strategic options much. For that matter it doesn't greatly enhance your tactical power either. Eventually someone is going to set off a nuke in some confrontation and find that it doesn't change the disposition of forces all that much. The dispersal of modern combat forces makes it hard to catch enough of them to make a permanent difference. If you're going to use one you'd better use a lot, but that puts you on the escalatory chain that ends with radioactive vitrified cities.

Having a few nukes is, however, a good way of allowing you to say this even louder which I think particularly in the case of North Korea is the main point. It's effectively a failed state already which extracts financial concessions on the basis of two things: its still potent conventional military power and the fact that its total collapse would cause problems for its neighbours which they'd rather not have. But conventional military power will dwindle eventually because starving soldiers don't tend to spend their time keeping up their equipment and training; and the power of moral blackmail will cease at the point those being blackmailed begin to reckon that the toll of innocents in the long-term will be less if the regime is allowed to/encouraged to collapse--short-term pain, long-term gain. A small nuclear arsenal maintains the status quo: effectively the answer, combined with some sort of blockade or inspection to prevent further proliferation, is to put the regime of Kim Jong Il on life support. For as long as he wants. The only 'wild card' here is China. Watch what they do. In the end though, beyond being publicly pissed off I don't think there's much that they can do either.

We can live with a nuclear North Korea--indeed, we have been for a while now, the tests confirmed what we'd already known. I'm not confident, however, that the same applies to Iran. 'Deterrence' works with North Korea in some form because the North Korean leadership doesn't want to die. Thank G*d for atheism! In the absence of an afterlife KJI would as likely as not prefer to go out the natural way: sipping cognac and watching tv in bed with company. This is not at all the attitude of Iran's leadership. The Ayatollah Khomeini put it clearly and chillingly:

'Either we all become free, or we will go to the greater freedom which is martyrdom. Either we shake one another's hands in joy at the victory of Islam in the world, or all of us will turn to eternal life and martyrdom. In both cases, victory and success are ours.'

My faith in deterrence in this case is not strong which inclines me to say 'Bomb Iran. Apologize afterwards' as Theo puts it. But there's a very good counter-argument (see this article, 'The Basis for Iran's Beligerence', by Shlomo Ben Ami, author of Scars of War, Wounds of Peace) to this which causes me to think otherwise. I'm glad I'm not the one who has to make this call. I suppose that if I were, as much as I admire Ben-Ami, I'd have to err on the side of caution. Alas, bombs away.

Still, as Theo points out, '...there is no reason that a military strategy cannot be fashioned to try and reduce the fallout, in the UNSC and Iran, from bombing. The West could say: "sorry but we had no choice and we did warn you."' I think a part of that strategy is making it a little clearer to the Iranian people that in a proliferated world where the Ayatollahs have control of nuclear arms they’ve more or less declared Iran to be poste restante for nuclear terror--if ’somebody’ sets off a bomb in a city we’re quite likely to assume Iran’s culpability and therefore that the appropriate return address reads: Tehran via Abadan, Ahvaz, Bandar Abbas, Bushehr, Isfahan, Hamadan, Kerman, Mashhad, Rasht, Shiraz and Tabriz. In other words, no one should be more concerned about WMD getting to non-state actors than Iranians. A nuclera Iran is reallly not in their interest right now when itchy trigger fingers abound. That Iran’s current leaders do not always seem to see the need for caution and less millenarian rhetoric concerns me. It should REALLY concern them too.

Update: Here's David Aaronovitch in the Times. Great opener:

'THE NORTH KOREAN regime is apparently so bad that even George Galloway has never been there to offer his support. Or maybe that’s because it’s so broke.'

I don't know enough to judge the science in these claims. I've been meaning to ask Prof Peter Zimmermann here in the Department of War Studies who does have that knowledge. Unfortunately, he's busy talking to journalists who aren't asking the right questions. Damn typical journos! I await enlightenment.

In the meantime, I'm amusing myself with question what does it matter? Answer (thus far): less than you might think.

The thing is that having nukes is not really as useful a thing as active proliferators reckon it is. It doesn't really expand your strategic options much. For that matter it doesn't greatly enhance your tactical power either. Eventually someone is going to set off a nuke in some confrontation and find that it doesn't change the disposition of forces all that much. The dispersal of modern combat forces makes it hard to catch enough of them to make a permanent difference. If you're going to use one you'd better use a lot, but that puts you on the escalatory chain that ends with radioactive vitrified cities.

Having a few nukes is, however, a good way of allowing you to say this even louder which I think particularly in the case of North Korea is the main point. It's effectively a failed state already which extracts financial concessions on the basis of two things: its still potent conventional military power and the fact that its total collapse would cause problems for its neighbours which they'd rather not have. But conventional military power will dwindle eventually because starving soldiers don't tend to spend their time keeping up their equipment and training; and the power of moral blackmail will cease at the point those being blackmailed begin to reckon that the toll of innocents in the long-term will be less if the regime is allowed to/encouraged to collapse--short-term pain, long-term gain. A small nuclear arsenal maintains the status quo: effectively the answer, combined with some sort of blockade or inspection to prevent further proliferation, is to put the regime of Kim Jong Il on life support. For as long as he wants. The only 'wild card' here is China. Watch what they do. In the end though, beyond being publicly pissed off I don't think there's much that they can do either.

We can live with a nuclear North Korea--indeed, we have been for a while now, the tests confirmed what we'd already known. I'm not confident, however, that the same applies to Iran. 'Deterrence' works with North Korea in some form because the North Korean leadership doesn't want to die. Thank G*d for atheism! In the absence of an afterlife KJI would as likely as not prefer to go out the natural way: sipping cognac and watching tv in bed with company. This is not at all the attitude of Iran's leadership. The Ayatollah Khomeini put it clearly and chillingly:

'Either we all become free, or we will go to the greater freedom which is martyrdom. Either we shake one another's hands in joy at the victory of Islam in the world, or all of us will turn to eternal life and martyrdom. In both cases, victory and success are ours.'

My faith in deterrence in this case is not strong which inclines me to say 'Bomb Iran. Apologize afterwards' as Theo puts it. But there's a very good counter-argument (see this article, 'The Basis for Iran's Beligerence', by Shlomo Ben Ami, author of Scars of War, Wounds of Peace) to this which causes me to think otherwise. I'm glad I'm not the one who has to make this call. I suppose that if I were, as much as I admire Ben-Ami, I'd have to err on the side of caution. Alas, bombs away.

Still, as Theo points out, '...there is no reason that a military strategy cannot be fashioned to try and reduce the fallout, in the UNSC and Iran, from bombing. The West could say: "sorry but we had no choice and we did warn you."' I think a part of that strategy is making it a little clearer to the Iranian people that in a proliferated world where the Ayatollahs have control of nuclear arms they’ve more or less declared Iran to be poste restante for nuclear terror--if ’somebody’ sets off a bomb in a city we’re quite likely to assume Iran’s culpability and therefore that the appropriate return address reads: Tehran via Abadan, Ahvaz, Bandar Abbas, Bushehr, Isfahan, Hamadan, Kerman, Mashhad, Rasht, Shiraz and Tabriz. In other words, no one should be more concerned about WMD getting to non-state actors than Iranians. A nuclera Iran is reallly not in their interest right now when itchy trigger fingers abound. That Iran’s current leaders do not always seem to see the need for caution and less millenarian rhetoric concerns me. It should REALLY concern them too.

Update: Here's David Aaronovitch in the Times. Great opener:

'THE NORTH KOREAN regime is apparently so bad that even George Galloway has never been there to offer his support. Or maybe that’s because it’s so broke.'

Tuesday, October 03, 2006

'End of History' and the 'Terrorism to Come'

In module 3 we've been having a discussion of the putative New World Order in the course of which wev've discussed, inter alia, Francis Fukuyama's End of History thesis. As so often happpens I have been reading something else which relates to that debate but not directly in a way that is appropriate for the ongoing discussion. But that's what thsi blog is for! I think some of you may find this Policy Review article interesting and enlightening of some of the things we've been discussing. The article discusses the work of the philosopher Alexandre Kojeve, a scholar with whom I was not previously familiar. The part which struck me as immediately relevant to us was thsi:

The philosophical basis for these deviations from Marxism is developed at length in Kojève’s treatise on law, Outline of a Phenomenology of Right, written during the Second World War but not published until the 1980s. There, Kojève points out that the End of History does not itself resolve the tension within the idea of equality — the ideal of equal recognition that is rationally victorious with the End of History embodies elements of market justice, equal opportunity, and “equivalence” in exchange (the “bourgeois” dimension of the French Revolution). But it also contains within it a socialist or social democratic conception of equality of civic status, implying social regulation, welfare rights, and the like. The Universal and Homogenous State — the consolidated global social and economic order — supposes some kind of stable synthesis between market “equivalence” and socialist equality of status. But it is not obvious, even to Kojève, when and how a permanent, stable, and universal (i.e., globally accepted) synthesis of this kind would come about.There's much more of interest there, including reflections on the EU, the boundaries of Europe and the conflict with Islam. Policy Review is an excellent journal. I find every issue has at least one article worth reading. The current issue also has a good piece by Walter Laqueur on 'The Terrorism to Come' . It's sobering reading. Laqueur articulates two points which I think are quite vital:

This dimension of Kojève’s thought is of great importance in understanding his vision of the postwar world. One reason it has received little attention is the way in which Francis Fukuyama popularized and adapted Kojève’s notion of the End of History. As the Cold War came to an end, Fukuyama took Kojève’s notion of a global, universal political and social order as a basis for understanding the direction of current events. According to Fukuyama, the remaining differences between nations after communism signify different paces or degrees of movement towards a common culture of liberal capitalism. In The End of History and the Last Man (Free Press, 1992), Fukuyama uses the image of a long wagon train strung out on a road. He writes: “The apparent differences in the situations of the wagons will not be seen as reflecting permanent and necessary differences between the people riding in the wagons, but simply a product of their different positions along the road” towards the “homogenization of mankind.” From a Kojèvian perspective, Fukuyama’s mistake was to understand the collapse of communism as the triumph tout court of liberal capitalism. This turn of events instead signifies the superiority of capitalism to Soviet communism in one, albeit crucial, respect: Unlike Soviet communism and its aparatchiks, capitalism and its real-world agents, the commercial classes, proved capable of compromise. Thus, while Soviet communism proved unable to engage in market reforms and internal liberalization without collapsing, Western societies proved agile at balancing the justice of the market with a conception of substantive equality — the latter perhaps rather minimalist in the case of the United States but still of enormous social importance.

Two lessons follow: First, governments should launch an anti-terrorist campaign only if they are able and willing to apply massive force if need be. Second, terrorists have to ask themselves whether it is in their own best interest to cross the line between nuisance operations and attacks that threaten the vital interests of their enemies and will inevitably lead to massive counterblows.

PBS Frontline

There's a lot of interest in an upcoming episode of Frontline, the excellent documentary programmme from the US public broadcaster PBS, abbout the Taliban. Unfortunately, it hasn't been put up on-line yet but I for one am eager to see it. If you aren't familiar with Frontline you should be. It's a bit like the BBC's Panorama in the UK, only a bit lengthier and for my money usually better--although Panorama is also very good. You can view entire episodes on-line which is extremely handy. What's also very useful is that they often post extensive research materials with every programme including transcripts of interviews, links to documents and so on. It's a very good resource. Have a look.

Monday, October 02, 2006

Boche or blighty?

Over on his blog Prof Theo Farrell's had a post on US attitudes toward those in uniform as seen in a recent Budweiser advert. 'Naff or right on?' he asked. Have a peek at it. Read the comments too. Very interesting. Then come back and read this article 'Boche or Blighty?

Excerpt:

Excerpt:

A paratrooper wounded in Afghanistan was threatened by a Muslim visitor to the British hospital where he is recovering.

Seriously wounded soldiers have complained that they are worried about their safety after being left on wards that are open to the public at Selly Oak Hospital, Birmingham.

On one occasion a member of the Parachute Regiment, still dressed in his combat uniform after being evacuated from Afghanistan, was accosted by a Muslim over the British involvement in the country.

"You have been killing my Muslim brothers in Afghanistan," the man said during a tirade.

Because the soldier was badly injured and could not defend himself, he was very worried for his safety, sources told The Daily Telegraph.

A relative of the Para said the man had twice walked on to the ward where two other soldiers and four civilians were being treated without once being challenged by staff.Quite the contrast, huh?

"It's not the best way to treat our returning men," he said. "They are nervous that these guys might attack them and, despite being paratroopers, they cannot defend themselves because of their injuries."

On Wikipedia

I love Wikipedia and I use it often. Not everyday, but certainly several times a week. There I've said it. I'm a 'full-grown' academic PhD in hand and I think Wikipedia is a fantastically useful thing. Use it. Better still contribute to it, for this is the really amazing thing about it.

But, there's always a but,

CAUTION: IT IS ALWAYS A BAD IDEA TO CITE AN ENCYCLOPEDIA IN ACADEMIC RESEARCH PAPERS.

Follow the link above. That's what Wikipedia has to say about its academic utility. I agree with everything said there and also with this Chronicle of Higher Education article and comments . Fundamentally, Wikipedia, like any encyclopedia, is only a starting for your research. To which I would add that owing to the way in which Wikipedia entries are authored they range in quality from exceptionally erroneous, even maliciously slanderous in at least one case, to exceptionally good. You must exercise critical judgment about what you read on Wikipedia--actually this is a good general rule but it's especially the case here. As it happens, I am impressed with the quality of Wikipedia entries in the areas in which I specialize. The problem more often than not is lack of depth and subtlety rather than factual inaccuracy.

There's an article by Marshall Poe in the September 2006 edition of the the Atlantic Monthly (subscription only, great magazine, you should consider subscribing) which I quote:

Wikipedia has the potential to be the greatest effort in collaborative knowledge gathering the world has ever known, and it may well be the greatest effort in voluntary collaboration of any kind.

I'm fascinated by the whole idea of the collaborative approach to knowledge-building which Wikipedia represents. I think it's a very big thing. Justt be cautious and sensible about how you use it and never rely on it exclusively.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)